JMS and Spring: Small Things Sometimes Matter

JmsTemplate and DefaultMessageListenerContainer are Spring helpers for accessing JMS compatible MOM. Their main goal is to form a layer above the JMS API and deal with infrastructure such as transaction management/message acknowledgement and hiding some of the repetitive and clumsy parts of the JMS API (hang in there: JMS 2.0 is on its way!). To use either one of these helpers you have to supply them with (at least) a JMS ConnectionFactory and a valid JMS Destination.

When running your app on an application server, the ConnectionFactory will most likely be defined using the JEE architecture. This boils down adding the ConnectionFactory and its configuration parameters allowing them to be published in the directory service under a given alias (eg. jms/myConnectionFactory). Within your app you might for example use the “jndi-lookup” out of the JEE namespace or JndiTemplate/JndiObjectFactoryBean beans if more configuration is required for looking up the ConnectionFactory and pass it along to your JmsTemplate and/or DefaultMessageListenerContainer.

The latter, JMS destination, identifies a JMS Queue or Topic for which you want to produce messages to or consume mesages from. However, both JmsTemplate as DefaultMessageListenerContainer have two different properties for injecting the destination. There is a method taking the destination as String and one taking it as a JMS Destination type. This functionality is nothing invented by Spring, the JMS specification mentions both approaches:

4.4.4 Creating Destination Objects Most clients will use Destinations that are JMS administered objects that they have looked up via JNDI. This is the most portable approach. Some specialized clients may need to create Destinations by dynamically manufacturing one using a provider-specific destination name. Sessions provide a JMS provider-specific method for doing this.

If you pass along a destination as String then the helpers will hide the extra steps required to map them to a valid JMS Destination. In the end a createConsumer on a JMS Session expects you to pass along a Destination object to indicate where to consume messages from before returning a MessageConsumer.

When destinations are configured as String, the Destination is looked up by Spring using the JMS API itself. By default JmsTemplate and DefaultMessageListenerContainer have a reference to a DestinationResolver which is DynamicDestinationResolver by default (more on that later). The code below is an extract from DynamicDestinationResolver, the highlighted lines indicate the usage of the JMS API to transform the String to a Destination (in this example a Queue):

protected Queue resolveQueue(Session session, String queueName) throws JMSException {

if (session instanceof QueueSession) {

// Cast to QueueSession: will work on both JMS 1.1 and 1.0.2

return ((QueueSession) session).createQueue(queueName);

}

else {

// Fall back to generic JMS Session: will only work on JMS 1.1

return session.createQueue(queueName);

}

}

The other way mentioned by the spec (JNDI approach) is to configure Destinations as administrable objects on your application server. This follows the principle as with the ConnectionFactory; the destination is published in the applications servers directory and can be looked up by its JNDI name (eg. jms/myQueue). Again you can lookup the JMS Destination in your app and pass it along to JmsTemplate and/or DefaultMessageListenerContainer making use of the property taking the JMS Destination as parameter.

Now, why do we have those two options?

I always assumed that it was a matter of choice between convenience (dynamic approach) and environment transparancy/configurability (JNDI approach). For example: in some situations the name of the physical destination might be different depending on the environment where your application runs. If you configure your physical destination names inside your application you obviously loose this benefit as they cannot be altered without rebuilding your application. If you configured them as administered object on the other hand, it is merely a simple change in the application server configuration to alter the physical destination name.

Remember; having physical Destinations names configurable can make sense. Besides the Destination type, applications dealing with messaging are agnostic to its details. A messaging destination has no functional contract and none of its properties (physical destination, persistence, and so forth) are of importance for the code your write. The actual contract is inside the messages itself (the headers and the body). A database table on the other is an example of something that does expose a contract by itself and is tightly coupled with your code. In most cases renaming a database table does impact your code, hence making something like this configurable has normally no added value compared to a messaging Destination.

Recently I discovered that my understanding of this is not the entire truth. The specification (from “4.4.4 Creating Destination Objects” as pasted some paragraphs above) already gives a hint: “Most clients will use Destinations that are JMS administered objects that they have looked up via JNDI. This is the most portable approach.” Basically this tells us that the other approach (the dynamic approach where we work with a destination as String) is “the least portable” way. This was never really clear to me as each provider is required to implement both methods, however “portable” has to be looked at in a broader context.

When configuring Destinations as String, Spring will by default transform them to JMS Desintations whenever it creates a new JMS Session. When using the DefaultMessageListenerContainer for consuming messages each message you process occurs in a transaction and by default the JMS session and consumer are not pooled, hence they are re-created for each receive operation. This results in transforming the String to a JMS Destination each time the container checks for new messages and/or receives a new message. The “non portable” aspect comes into play as it also means that the details and costs of this transformation depend entirely on your MOM’s driver/implementation. In our case we experienced this with Oracle AQ as MOM provider. Each time a destination transformation happens the driver executes a specific query:

select /*+ FIRST_ROWS */ t1.owner, t1.name, t1.queue_table, t1.queue_type, t1.max_retries, t1.retry_delay, t1.retention, t1.user_comment, t2. type , t2.object_type, t2.secure from all_queues t1, all_queue_tables t2 where t1.owner=:1 and t1.name=:2 and t2.owner=:3 and t1.queue_table=t2.queue_table

Forum entry can be found here.

Although this query was improved in the latest drivers (as mentioned by the bug report), it was still causing significant overhead on the database. The two options to solve this:

- Do what the specification advices you to do: configure destinations as resources on the application server. The application server will hand out the same instance each time, so they are already cached there. Even though you will receive the same instance for every lookup, when using JndiTemplate (or JndiDestinationResolver, see below) it will also be chached application side, so even the lookup itself will only happen once.

- Enable session/consumer caching on the DefaultMessageListenerContainer. When the caching is set to consumer, it indirectly also re-use the Destination as the consumer holds a reference to the Destination. This pooling is Spring added functionality and the JavaDoc says it safe when using resource local transaction and it "should" be safe when using XA transaction (except running on JBoss 4).

The first is probably the best. However in our case all destinations are already defined inside the application (and there are plenty of them) and there is no need for having them configurable. Refactoring these merely for this technical reason is going to generate a lot of overhead with no other advantages. The second solution is the least preferred one as this would imply extra testing and investigation to make sure nothing breaks. Also, this seems to be doing more then needed, as there is no indication in our case that creating a Session or Consumer has measurable impact on performance. According to the JMS specification:

4.4 Session A JMS Session is a single-threaded context* for producing and consuming messages. Although it may allocate provider resources outside the Java virtual machine, it is considered a lightweight JMS object.

Btw; this is also valid for MessageConsumers/Producers. Both of them are bound to a session, so if a Session is lightweight to open then these objects will be as well.

There is however a third solution; a custom DestinationResolver. The DestinationResolver is the abstraction that takes care of going from a String to a Destination. The default (DynamicDestinationResolver) uses the createConsumer(javax.jms.Destination) on the JMS Session to transform, but it does however not cache the resulting Destination. However, if your Destinations are configured on the application server as resources, you can (besides using Spring’s JNDI support and injection the Destination directly) also use JndiDestinationResolver. This resolver will treat the supplied String as a JNDI location (instead of physical destination name) and perform a lookup for you. By default it will cache the resulting Destination, avoiding any subsequent JNDI lookups. Now, one can also configure JndiDestinationResolver as a caching decorator for the DynamicDestinationResolver. If you set fallback to true, it will first try to use the String as a location to lookup from JNDI, if that fails it will pass our String along to DynamicDestinationResolver using the JMS API to transform our String to a Destination. The resulting Destination is in both cases cached and thus a next request for the same Destination will be served from the cache. With this resolver there is a solution out of the box without having to write any code:

<bean id="cachingDestinationResolver" class="org.springframework.jms.support.destination.JndiDestinationResolver"> <property name="cache" value="true"/> <property name="fallbackToDynamicDestination" value="true"/> </bean> <bean id="infra.abstractMessageListenerContainer" class="org.springframework.jms.listener.DefaultMessageListenerContainer" abstract="true"> <property name="destinationResolver" ref="cachingDestinationResolver"/> ... </bean>

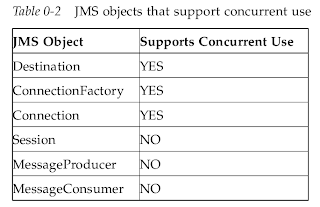

The JndiDestinationResolver is thread safe by internally using a ConcurrentHasmap to store the bindings. A JMS Destination is on itself thread safe according to the JMS 1.1 specification (2.8 Multithreading) and can safely be cached:

This is again a nice example on how simple things can sometimes have an important impact. This time the solution was straightforward thanks to Spring. It would however been a better idea to make the caching behaviour the default as this would decouple it from any provider specific quirks in looking up the destination. The reason this isn’t the default is probably because the DefaultMessageListenerContainer supports changing the destination on the fly (using JMX for example):

Note: The destination may be replaced at runtime, with the listener container picking up the new destination immediately (works e.g. with DefaultMessageListenerContainer, as long as the cache level is less than CACHE_CONSUMER). However, this is considered advanced usage; use it with care!