Git: Keeping Your History Clean

As we migrated lately from subversion to git, it was clear from the beginning that we needed some extra rules for keeping the history clean. The first thing that we stumbled upon were the so called automatic ‘merge commits’ performed by git.

In case you don’t know what they are; imagine a typical closed project setup with a central repository to share work between multiple developers. Now suppose developer John committed and pushed some changes. In the mean time there is Jim developing something on the same branch on his local repository. Jim has not pulled from central, so the central repository is still one commit ahead. If Jim is ready with his code he commits the changes to his repository. When he now tries to push his work to central, git will now be instructing Jim to pull first (to get the latest changes from central) before he’ll be able to push again. From the moment Jim does a “git pull”, a merge commit will be made by git indicating the commit done by John.

This is new when coming from subversion as with svn you won’t be able to commit in the first place. You would first have to “svn up” before doing “svn commit”, so your changes would still be in your local working copy (unlike with git where they are already committed to your local repository). To be clear: these merge commits don’t form a technical issue as they are “natural” (to a certain extend) but they do clutter the history a lot.

To show how this would look in our history, we’ll simulate this locally using three repositories (central, a bare git repo and john/jim both 2 clones of central). First John commits and pushes john.file1. Then Jim creates and commits jim.file1. If Jim now tries to push his work, he’ll be getting:

! [rejected] master -> master (fetch first) error: failed to push some refs to '/tmp/central/' hint: Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do hint: not have locally. This is usually caused by another repository pushing hint: to the same ref. You may want to first merge the remote changes (e.g., hint: 'git pull') before pushing again. hint: See the 'Note about fast-forwards' in 'git push --help' for details

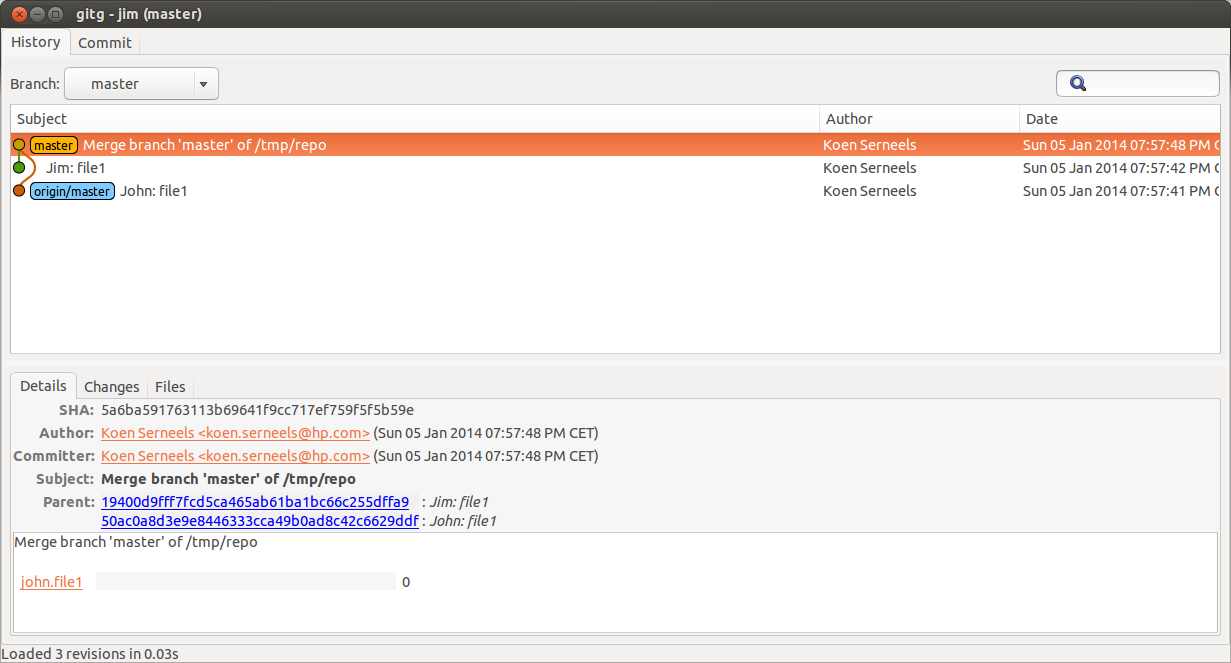

If Jim would simply ‘pull’ the changes from origin would be merged and Jim will on his turn be able to push his changes to central. All good. However, our history will now contain the so called merge commit as highlighted below:

As said before, this is happening because the local branch has advanced, compared to central, with the commit of Jim. Therefore git can no longer do a fast forward. Git will (by default) basically be merging in the changes it received from origin and thus has to make a commit. Altering the commit message is still possible, but you’ll end up with a actual commit either way. The result is that the change appears to be done twice when looking at the history which can be quite annoying. Also, if the team is committing/pushing fast (as they should) a lot of these entries will appear and really start to clutter the history.

A solution for this is to rebase instead of merge. This can be done by doing:

git pull --rebase

When using ‘git pull’ git will first bring the changes from origin to the local repo and then (by default) merge them into your local working copy. If rebasing instead, git would (temporary) undo your commits, fast forward your branch and the re-apply your changes. These commits will be new commits as the old ones are thrown away. They get a new SHA1 identifier and all the likes.

Rebase is however only a solution in particular scenario’s, so we would certainly not make it the defaul for everything. From the Git book :

If you treat rebasing as a way to clean up and work with commits before you push them, and if you only rebase commits that have never been available publicly, then you’ll be fine. If you rebase commits that have already been pushed publicly, and people may have based work on those commits, then you may be in for some frustrating trouble.

As long as you are not playing with commits that have already been pushed out to others there is no problem. We are working in a standard closed Java project with a single central repository that is adhering to these rules:

- Developers don’t synchronize repositories directly with each other, they always go via central

- Developers don’t push to anything else then central

In this case there is no risk for commits to be made public before rebasing them using git pull. Doing so we can safely make ‘git pull’ rebase automatically for our project master branch using:

git config branch.master.rebase true

Another problem that caught my attention (being triggered when looking into the automatic merge commit problem) is that our branching structure was not optimal. We are using a feature branch approach but as feature branching (and merging) with subversion comes at high pain we only did it if really necessary. However, when using git creating branches and merging is just a breeze so we changed our rules to be more natural:

- There must be a (in our case; more) stable master branch on which only completed features will be merged into. Theoretically speaking, no one works directly on the master. This implies that almost all work is executed on feature branches

- Releases are made from a release branch which is a copy of the master branch at the point the release is triggered

- The master log must be as clean and straightforward as possible: each feature being merged back into the master must be exactly one commit with the log message stating the ticket and the history showing all changes relevant to that feature.

When working like this chances that you get automatic merge commits are very minimal. Reintegrating features branches would become an (almost) atomic operation avoiding (nearly) any risk for having those automatic merge commits, even when not rebasing. Of course, some rules must be followed before integrating:

- Code reviews must have been done on the feature, one way or the other

- The feature branch must first be updated with the latest version of the master. This happened regularly while developing the feature (you want to be as up to date with the master as possible) but certainly a last time before you’re planning to reintegrate the feature. With git this means you simply do “git merge master” while on the feature branch and it will complete in matter of seconds. Doing so conflicts (of other features that have been reintegrated in the master in the mean time) can be resolved while on the feature branch.

- Tests and the likes must be run on the feature and must be 100% success before reintegrating the feature.

When following these rules the following 3 lines will reintegrate the feature succeeding one after the other making it an almost atomic operation and thus practically making rebase unnecessary:

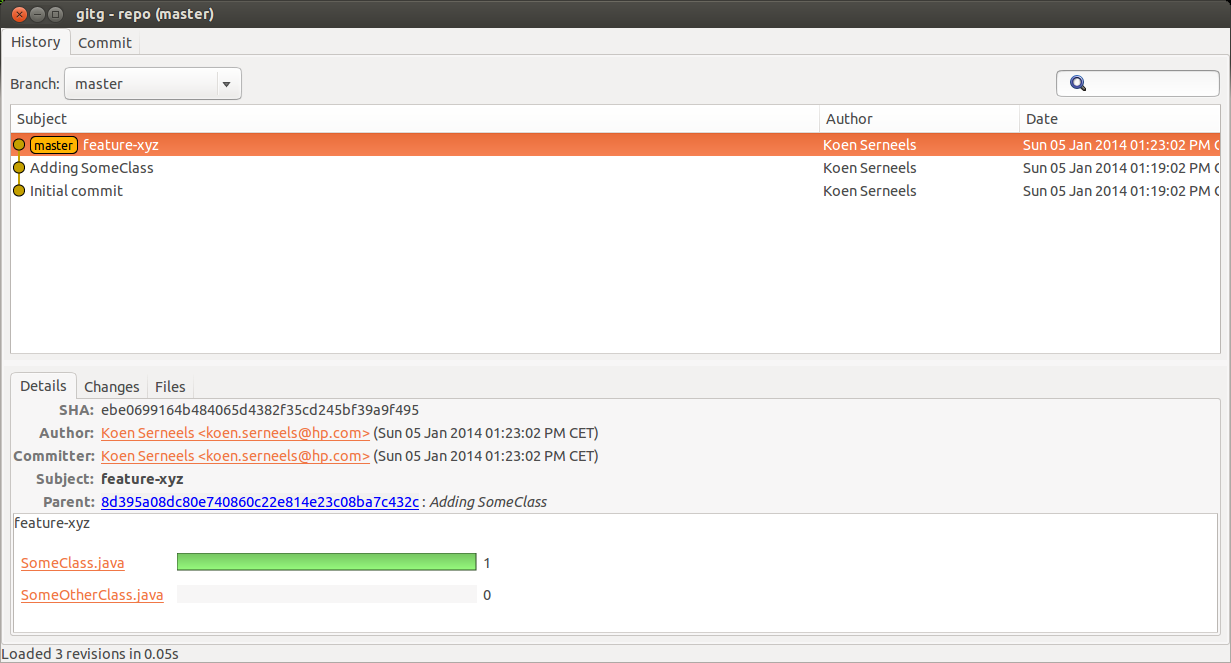

git checkout master git pull git merge --no-commit --squash >feature branch< git commit -am "FEATURE-XYZ" git push

Now, even when working like this we leave rebase set to true for the master as it is still possible for the remote to change in the meantime. In the event this happened (after committing the merge) a simple ‘git pull’ (with implicit rebase) will solve the problem so that our push will succeed.

Other important rules for keeping clean history are making use of ‘–squash’ as used above:

The –squash will drop any relation to the feature it came from. Doing you can create a single commit that contains all changes without taking any other history from your feature into your master. This is mostly what you want. A feature can contain a lot of “junk” commits which you don’t want to see on your master. In the typical case you simply want to see the result and not the intermediates. Also note that –squash also implies –no-ff as git will not fast forward even if it’s possible (otherwise you would not be able to get a single merge commit in the first place).

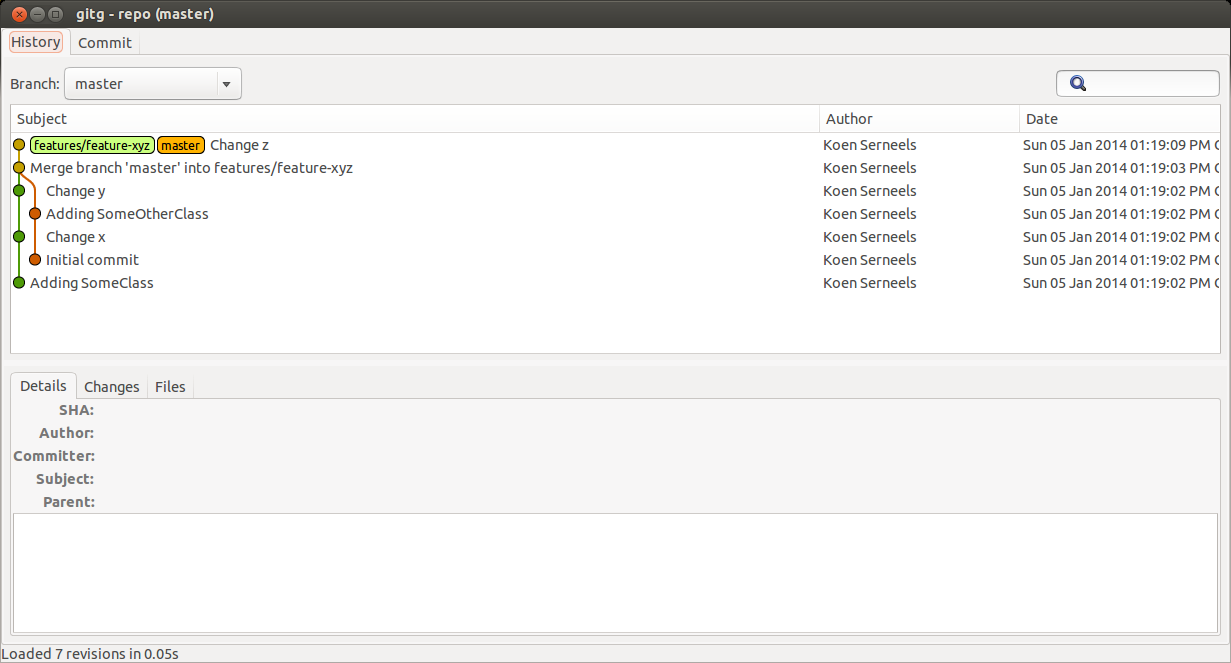

To illustrate this, when we would simply be reintegrating using ‘git merge’ the history would look like this:

<

Since the feature was updated with the master before reintegrating, git performed a fast forward. If you look at the history the commits from the feature will be in-lined into the master. This gives the impression that all work had been done on the master. We can also see all intermediate commits and other non interesting commits such as the merge commits from updating the feature with the master. Not a real problem, but to see what has been changed you would (possibly) have to go through a lot of clutter and look at each individual commit to get the big picture, which is not what you typically want.

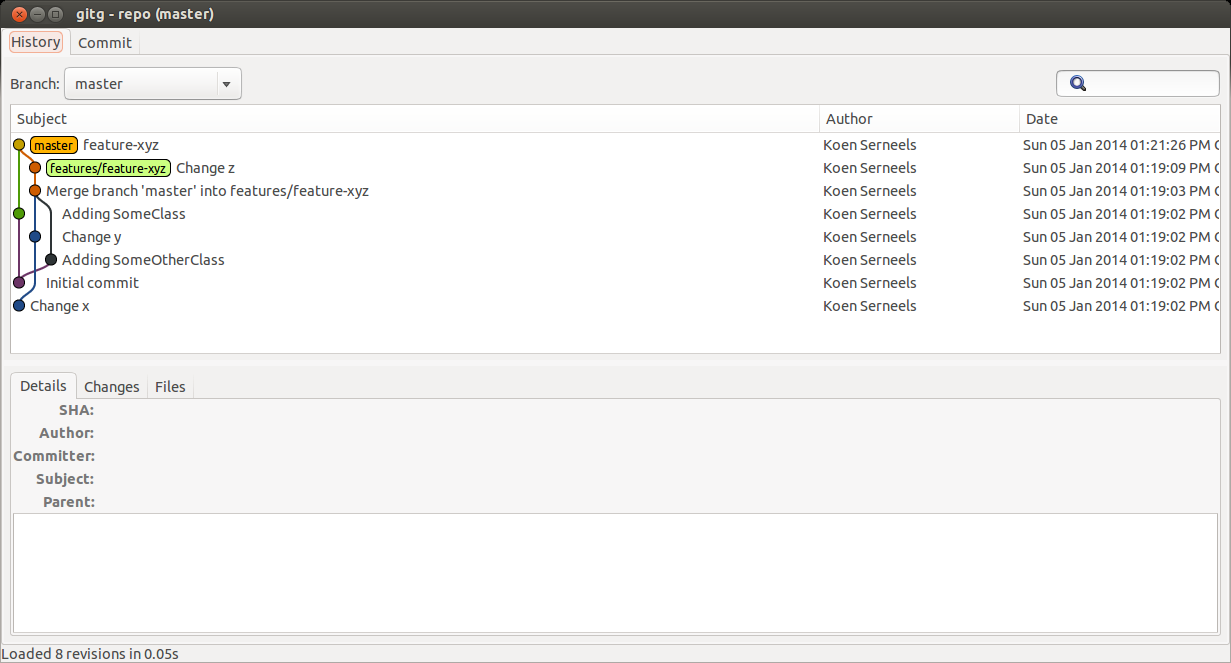

When disabling fast forward (git merge –no-ff) the history would look like this:

A bit better as we can now see which commit are related to feature-xyz. However, the changes are still scattered over different commits and we still have other commits in which we’re not interested in. Someone needing history of feature-xyz is normally not interested in how the feature evolved or how many times a class was refactored. Typically you’re only interested in the end result: the changes/additions that will be added to the master branch. By adding “–squash” we accomplish a clean and single commit in our master which list all changes for that feature:

Note that the history of the feature is not lost of course. You can still go back the feature branch and look at the history if that would be necesary.

The –no-commit is convenient if you are skeptical (like me) and want to review to changed/added files for a last time before making the reintegration final. If you leave this option out Git will directly commit the merge without leaving you time to do this final check.

On a side note: to perform code reviews on features before they can be reintegrated I tend to create a (local only) branch of the master being a kind of ‘dry run’ branch. The feature is then reintegrated on that review branch (without committing changes) just to perform code review. Doing so all changed files will be marked dirty by your IDE making it easy to see what has actually changed (and to compare them with the HEAD revision). Then I gradually commit changes as I reviewed them. When code reviewing is done, the merge will be completely committed on the the review branch and it can then be merged back to the feature branch before it’s finally reintegrated into the master branch. I (normally) don’t make the review branch remotely visible, and just delete them locally after reviewing is done. Theoretically one can also merge the review branch back to master directly, but since this review branch will be deleted the real feature branch would never got the changes performed by the code review and you would be losing that history.